How to Map

“Over 100 countries”, he said when I had asked him how many places he had visited in his lifetime. He didn’t even appear that old.

This was last month, while I was in London for a close friend’s wedding. I was strolling the streets near the popular Borough Market, south of the Thames river, on a sunny weekend morning. I was walking alone, without my phone in hand, having left my hotel with the intention to get lost and with the curiosity to see what I might discover.

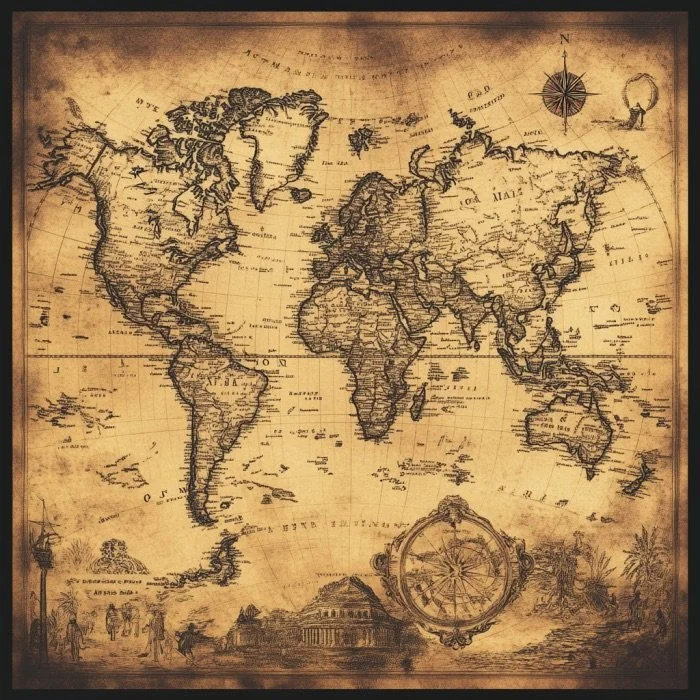

A beautiful old school map caught my attention in the window of a tiny little shop. Without thinking, I walked right in and began touching the paper. It was soft, almost felt-like, and pleasant for my fingertips. I then noticed that it was a map of the world, drawn in 1797.

This was a time before air travel. Before satellite systems. Before electricity. Before cars. Before Google Maps.

I began to marvel for a brief moment at the ingenuity and intelligence previous generations, centuries ago, demonstrated. I can hardly remember my own phone number or figure out how to turn off some annoying feature on my iPhone without first asking chatGPT for step-by-step instructions. And I studied Software Engineering at a good school, and ran a technology business for fifteen years. Yet over two hundred years ago, someone was drawing by hand a map of the entire world, likely by studying hundreds of versions drawn by people before.

“Where are you from?”

My train of thought was interrupted by what I assumed was the owner of the map store I was silently standing in.

“Canada, although originally my family is from India,” I told him with a smile.

He turned and walked over to the other side of the tiny shop, flipping through beautifully designed decorative envelopes and pulled one out enthusiastically.

He walked back to me and quietly opened the large envelope, took out a folded piece of paper and began to open it slowly. It was a map of India from the early 1800s.

I had never seen one before. This was India under British rule. This was India before partition that created borders with Pakistan and Bangladesh. This wasn’t the India I had grown up learning about and visiting often. I was curious.

As we started to chat some more, and the many cities and countries I have lived in started to come out, new maps were shown to me. Each one captured my curiosity, showing me something I didn’t know about a place I thought I knew.

“It’s a different way to look at things,” he remarked, not realizing that I received his casual comment not literally but metaphorically.

So much of my experience of life is based on my perspective of life. And so much of my perspective is shaped by the culture, community and conditioning that I choose. These influences, like the old hand drawn map I was holding in my hand, show me something that I didn’t know. And they are full of biases, and that’s totally fine.

It’s less about trying to find an unbiased or objective viewpoint, as that may not exist, but rather to understand the biases and subjective nature of everything that I encounter.

This thought may have been deeply concerning for me even a decade ago, as the culture I had learned in school taught me that there must always be a single right answer to every question. I have since learned that’s not fully true.

Learning about the map store owner’s passion for maps that had taken him to over one hundred countries in search of the most rare and interesting maps, only to be redesigned by him in his unique style, I can’t help but think of the different lenses in which we view the same thing.

For example, if I find a cookie disgusting and you find it delicious, which one is it? Is the cookie disgusting or delicious? It depends on who’s asking. There is no single answer. There may be a popular answer, but it is a subjective question that deserves a subjective answer.

I have long appreciated the wisdom ‘pay attention to what you pay attention to’, meaning everything is less as it seems and more as I seem it to be. My intention is to choose my influences and biases, versus trying to eradicate them. All the while being open to discovering something new about something I may perceive to be old, like what a map of India looks like.

Looking now at a map of New York City from 1859 in my hand, I could spot immediately the street I had lived on and the one where I had an office. But they seemed a lot further from one another in proportion than I remembered from just a few years ago. Drawing a map without the technology and tools we have today was clearly a subjective exercise back then. And I suspect everyone was fine with that.

I then saw a map of New York City from the early 1900s. Here the proportions started to look more inline as I had experienced them to be. An evolution of still a subjective exercise.

Learning to tolerate different perspectives, like different maps of the same place drawn at different times, requires a deeper understanding and belief in the inherent subjectivity that exists everywhere. It is this understanding that is the root of the tree that allows a society to flourish and grow strong together.

Everyone is not going to think and believe the same things and waiting or wanting them to is a recipe for frustration. We all have our own subjective perspectives, influenced by the unique circumstances and conditions that we find ourselves in. Be it place, time, or people. They are all unique, and shape us in unique ways.

The same goes for me as an individual. What I thought, said or did a decade ago will be different than how I am now. And dare I say how I will be in the future.

After all, the universal truth that I was reminded of looking at different maps of the same place is that everything changes. I may not be in control of how, or when, or even in which ways, but I can accept that everything changes. For me, maps are now a symbol of change.

And that is how I learned to map.